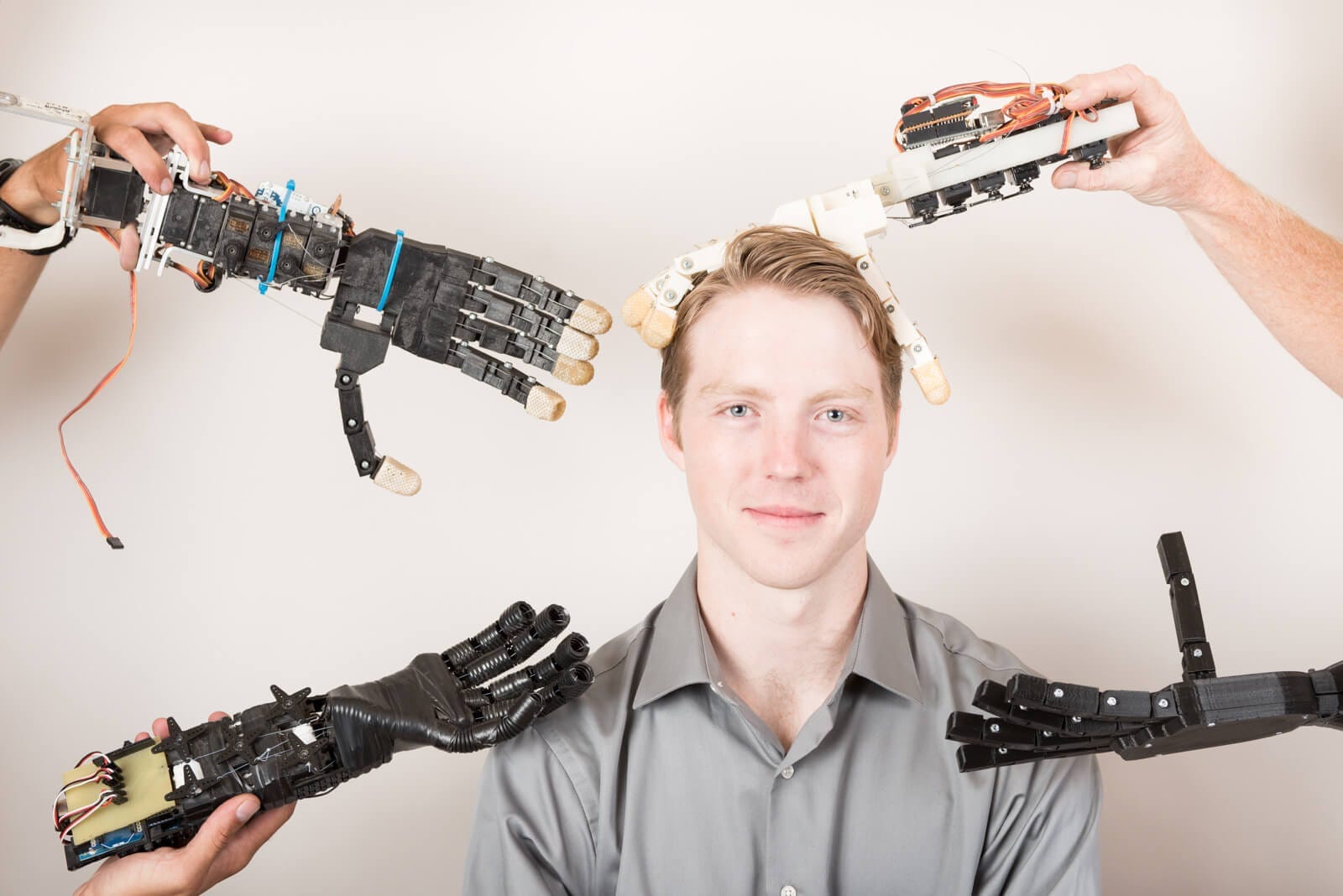

Easton LaChappelle

Easton LaChappelle is the founder of Unlimited Tomorrow, a company revolutionizing the world of medical prosthetics.

When he was just 14, Easton LaChappelle built his first working robotic arm out of fishing line, LEGO, and off-the-shelf electric tubing. The 10 years since then have been a whirlwind of activity, from showcasing his work to President Obama at the White House science fair, to getting seed funding from motivational speaker Tony Robbins, to starting his company Unlimited Tomorrow and moving it from Colorado to Rhinebeck.

It’s a cold day in early December when I drive to Unlimited Tomorrow’s headquarters, just past downtown Rhinebeck. The building looks unassuming, and from the outside I have trouble imagining it as the home base of a company about to change the world of medical prosthetics. That changes as soon as I step inside.

The space feels very tech-company-meets-Hudson-Valley: concrete floors, wooden walls, lots of whiteboards and desks and people working on CAD software. In the corner past the entrance is a powered exoskeleton. Through a doorway, I can see an array of industrial-grade 3D printers. I’m starting to get an Iron Man vibe.

That vibe continues as I meet Easton. He’s friendly and dynamic, and his passion and enthusiasm for his work are immediately evident — I can see why Tony Robbins called him “the next Elon Musk.” (No pressure.) He shows me around the office and I get to see the history and future of Unlimited Tomorrow and — it seems likely — the entire prosthetics industry.

Easton: This is the first prosthetic hand I made, back when I was 14 in Colorado. Lots of electrical tubing, fishing line as the tendons, servo motors, LEGO as plastic supports, Arudino board. I made my first printed circuit board — it’s funny looking back, I didn’t reverse it, so my name on it is spelled backwards.

Easton’s first prosthetic handAt the time this was just for fun, out of boredom. “How can I make something cool and interactive? How can I make something open-ended that isn’t just software and electronics, but is robotics and mechanics and systems design and all these things?” At the time, I was making a robotic hand that was controlled by a control glove. You might recognize this — it’s a Nintendo Power Glove that I bought off eBay. I cut off the whole forearm. This has flex sensors embedded within it.

That’s such a great MacGyver hack, using an old Power Glove.

It’s funny, the Power Glove didn’t catch on. They’re around $50 on eBay — it’s actually cheaper to buy a Power Glove than to buy five flex sensors. It was ahead of its time.

You can see a natural progression. I stumbled upon a passion for creating things and turning ideas into reality, and I saw so many ways to improve on the original design. Adding an opposable thumb, individual finger joints, adding more motors, getting clever with software and electronics and the control systems behind it.

This is when MakerBot Industries was really the only company in the consumer space. They had the old CupCake, the laser-cut 3D printers. I didn’t have one of these machines so I had to send a quote out, and I was getting quotes of $500 just to print a hand. Being 14 or 15 years old I didn’t have that kind of money, so I turned to social media and I found one of the early employees working at MakerBot who threw it on the printer one night, so I only had to pay for shipping.

As you can see, I still got clever with it, using rubber bands to help spring fingers back. I started working with aluminum, pretty much turning my bedroom into a lab. I’d work into the middle of the night.

I grew up in a small town called Mancos, population of about 1,200 people. My graduating class was around 23 kids. I was bored a lot.

So I’m guessing you didn’t have a 3D printing lab or anything.

In a way I look back and it’s not great there was no support and no resources, but to its credit, it motivated me to go out and learn on my own. That’s how I found my passion and stumbled upon everything. I found the open source community which has always been an amazing knowledge base.

Growing up in Colorado, I started making these things and entering them into science fairs. In 2012, I met a small girl at a state science fair who was missing her right arm and was wearing a prosthetic device. It was the first time I saw this type of technology, and I got to talk to her and her parents about the process, how it was made, how much it cost. It completely blew me away — it was my “aha” moment.

It took months to create a prosthetic device for a growing child, and it cost $80,000. She was probably one of the few children to have this kind of device, and on top of that, it was a claw with one motion and a sensor. That really opened my eyes — I had a full robotic arm with individual fingers that could toss a ball and interact with people, and then she had this $80,000 claw… it’s night and day.

After I met her, I started making another arm that was a more prosthetic-centered design — it’s the left arm on that skeleton, with the glove on it. It’s more ergonomic, more organic-looking. This was my entry into muscle control and brainwave systems. I started using EEG headsets and sensors to control the device, and started increasing functionality across the board. That hand actually shook hands with President Obama at the White House science fair. It was a really amazing moment.

That was my first taste of bigger systems design. This is around 2013, when Unlimited Tomorrow was being formed. Media started exploding — there was the White House science fair, I was doing an internship at NASA, I was traveling around doing keynotes. It was the craziest year of my life. I was around 17. I was invited to give a TEDx talk in Denver and Tony Robbins, who became our founding investor and partner, saw that and gave me a call one day, saying: “I can’t believe you’re still working out of your bedroom at your parents’ house. I need to help you take this to the next level.” He provided startup capital and some guidance and mentorship to help make that happen.

This was the first real prosthetic device that we made, for a 10-year-old girl named Momo. We did this amazing documentary with Microsoft. They helped out with a lot of this.

Microsoft gave me access to their secret R&D lab. I had access to the best 3D printers in the world, and some engineering resources, to make all this happen. It really started validating our business model, which was sending a 3D scanner — at the time it was a webcam, actually — down to Florida where Momo lives. The first time I gave her this device was the first time I ever had a conversation with her and interacted with her in general. That was really validating — making a very personalized medical device for someone I’ve never even met or had a conversation with. That set the bar for us.

This is where we are today. Our current device is under a pound-and-a-half. Individual finger control, custom actuators, electronics, and batteries all in the palm of the hand. For a seven-year-old to a fifty-year-old, it’s all the same components — it’s all modular in that sense — and the forearm is basically empty. It links to a socket.

You must know a decent amount about human physiology, then. You must have a sophisticated mental model of the arm.

The human hand consistently blows me away, every day. It’s nearly impossible to truly replicate the human hand. It’s insane how it works.

We know the general shape and the function that we’re trying to achieve. Now how do we do that mechanically? Even to rotate your wrist, you have two bones that criss-cross. Trying to replicate that mechanically isn’t practical. You have to keep that in the back of your mind, but also invent new ways to maintain aesthetics.

Easton and I walk into the R&D lab portion of the facility, where he shows me their industrial-grade 3D printers.

Almost everything you see here is 3D printed; these literally come off the machine looking just like this. It’s one thing to print something like this and keep it in a display case where no one can really touch it; it’s another thing to print something like this with the aesthetics and have it functional so you can give it to a child and they can play with it. You can see some of the accuracy of what we can print with — really crazy detail. We can print things already assembled, with pieces interlocked, such as fully-functional backpack buckles.

The philosophy is, how can we send 1,000 arms to anywhere in the world, and someone can put it on and have a personalized result without a clinician being physically involved? That’s a really hard task, because up until now you would spend months with a clinician. We had to really take a step back, reinvent the technology, the delivery mechanism, and the whole business model. So we’re going direct to consumer while bringing in clinicians internally to make sure we’re staying ethical and safe. And then direct-to-consumer e-commerce, so an amputee can go to the website and fill out an eligibility form. If they’re eligible, they’re sent a 3D scanner, they take a 3D scan of the arm that they’re missing, take a scan of the full arm so we have a full image, match skin tone along the way.

These are some of the iPads we use as 3D scanners. These are insane, for the cost — that was one big area that we were testing. Can someone’s parent who doesn’t know how to use a cellphone use this to 3D scan their child’s limb? Turns out they can! We’ve done a lot within the mobile app development to make that happen.

For us, it’s about accessibility and affordability. Affordability helps unlock accessibility.

Being able to 3D print quickly and on-site… does that mean you’re able to move more of the process out of CAD software and into physical testing?

Yeah. We 3D print something every night, whether it’s for production or R&D. These machines let us stay nimble. You can fit a lot into these machines. It’s actually the same cost and time to print one bike pedal as it is to print 100 bike pedals.

You’re almost moving to the zero-marginal-cost economics of digital products, but for physical products.

Our inventory is mainly electronics and nuts-and-bolts; everything else is on-demand printed, and it’s fast enough that it allows us to do that. There’s very little inventory and overhead for what we do.

We can 3D print cages around things, so if we have a bunch of fingernails or other small pieces that get lost in the machine, we just 3D print cages around them so they come out together.

These are some disposable cages, so you can print fingernails in there and then cut away the cage after you take it out of the machine.

How many people work at Unlimited Tomorrow?

Twelve right now. We’re actively hiring about four other positions, and set to continue growing in 2020.

A really big piece of that is we have really amazing partnerships with HP, Microsoft… some of the CAD software we use is around $20,000 a seat, so we have a partnership with a company so we get that for free. That’s been really great.

We also have really solid marketing and storytelling, so when someone is talking about 3D printing and AI and all these different concepts, our products really help people to understand that.

We’re about 80% engineers right now, so we’re actively growing and actively hiring marketing staff to help us grow and take this to market. We’re looking to go to market early to mid 2020.

Does it ever create challenges that you can’t test the devices yourself?

Yes, and that’s why we’ve created a test group of 100 — we have a lot of children, adults, veterans, people from 15 different countries and all walks of life. It’s different if someone is born without an arm than if they lost an arm through an injury or disease. No two cases are the same. We’re trying to make universal technologies to solve those challenges and physical differences.

We also have wireless charging — you put this on the charger, and there’s a coil in the palm of the hand. We’ve been getting very creative with our mechanics.

How long does it last on a charge?

That’s a really big piece. We were at a nonprofit conference a few months ago, and a lady came up to us saying, “I have a $120,000 prosthetic limb, but the battery just died.” It was 11 in the morning, and it was in her car — she wasn’t wearing it. The industry standard is a couple of hours. It’s awful. And it’s heavy as well — it’s like an old cellphone compared to the phones we have now.

We get a multi-day battery life. What sets us apart from anyone else in the industry is that we’ve created the whole solution from the ground up. Conventionally, one person makes the socket, one person makes the hand, one person makes the battery, the muscle sensors, and each of these components alone are a couple of thousand dollars. You get a really messy result that’s just a bad result for the patient. Half the people who have a device don’t wear them because of these problems — the adoption rate is horrible. We’re doing a lot to try and combine both worlds, function and aesthetics.

Our goal is to make this as affordable as possible and we are looking to launch our product for around $10,000. We also want to encourage growth in children so when they outgrow a device it will be even cheaper for them to get an upgrade.

Why Rhinebeck? How did you wind up here?

I was having a lot of challenges in Colorado. I’d moved up to the Fort Collins area, just north of Denver, with the hopes of being able to grow and expand. Before that I was in Southwest Corner; the nearest interstate was a couple of hundred miles away, I was very limited and having trouble finding a good core team and a commercial space where I could knock down walls and expand. Ultimately, I found some amazing commercial space, but I’d have to sign a 3-year lease, and would probably outgrow that space in 6 months. That was a major constraint.

Tony Robbins connected me with one of my mentors, Jonathan Cohen. He actually owns this building, and the timing worked out beautifully. I was hitting my head against the wall trying to grow and expand a company where I was, and Jonathan said: “I just bought a 6,000 square foot building. You can have free rein.” We completely updated this building, tore up the carpet, polished the floors, it’s night and day from what it used to be. And proximity to New York City and the Boston area and MIT!

There have been an incredible amount of incentives from New York State that have helped us to grow and expand, from equipment purchases to R&D credits to marketing opportunities. We’re becoming a poster child for the Hudson Valley retaining startups.

What’s been your favorite thing about being based in the Hudson Valley?

Growing up in Colorado, I love the combination of being able to go mountain biking or skiing, but then also being able to jump on a train and get to Penn Station in an hour-and-a-half. It’s the best of both worlds.

As we grow and look for talent, that’s all very helpful too.

What have been some challenges of being located in the Hudson Valley?

Not a lot. If anything, I think if we’d moved to a city there’d actually be less opportunity in terms of state financing options and grant opportunities. Because we’re in an area where IBM pulled out and really impacted the economy, there’s a lot of money set aside to help rejuvenate this area, and we fit into that.

Outside of work, where in the Hudson Valley do you like to go?

I live right outside of Kingston, nestled in the woods. I’m very close to Woodstock, which is a very fun place. Besides that, we always go up to the Catskills and venture down to Minnewaska State Park. There’s a lot to stay busy.

What else would you want people to know?

We’re a fast-growing company doing some incredible things, and we’re right around the corner from downtown Rhinebeck. You don’t have to be in a big hub like Silicon Valley to do these things. I want people to know that.

This interview has been edited.