Brad Teasdale

Garrison-based artist Brad Teasdale's unique furniture fuses Hudson River driftwood with concrete made from local materials.

When I met designer Brad Teasdale at his studio in mid-September, I asked him why he calls his signature pieces “mermaid benches.”

He replied: “Half land, half water.”

His benches and tables are a fusion of driftwood and concrete, all sourced locally — the wood comes from the Hudson, and the concrete is produced using Hudson Valley sand. The concrete, I should say, is unlike any concrete I’ve seen or felt before — rather than the coarse and gravelly material I’m accustomed to, it’s silky-smooth and completely uniform.

I first became aware of Brad’s work from a piece in Hudson Valley Magazine. After corresponding via email, I drove down Route 9D from Beacon to Garrison to see his work in person and visit his studio, a workshop set back in the woods alongside his home and within earshot of a forest waterfall.

We walked behind the workshop to a porch covered with massive pieces of driftwood, slowly drying out for eventual use.

Local Wood and Hudson Valley Terroir

Brad: This wood is called black locust, and it’s incredible durable. Before concrete was used in building, black locust was prized for foundation posts and fenceposts because it doesn’t rot. I typically only work with locust, ash, or cedar.

Over the years I’ve just been accumulating some awesome wood. This is all driftwood. I love working with driftwood. It’s all from the Hudson.

All these pieces are driftwood, so they don’t rot. It’s hard to tell how old some of these pieces are.

Why don’t they rot?

Most wood does rot, and then black locust and cedar… if you think about Japanese hot tubs, for instance, they’re made out of cedar. In Japan they call it hinoki, but it’s essentially cedar. I think it’s certain alkaloids that are in the woods, certain antibacterial alkaloids. I think that’s part of it.

This monster over here is black locust and weighs about 300 pounds.

I’m impressed you were able to get this out of the water.

This took a bunch of guys.

Essentially, I let the wood season, and then I’ll mill it down. The roots of the stump create half of the legs of a bench.

I’ve been working with concrete for about 20 years. When I was in my early 20s I worked with a stone mason, and we were doing construction-based work, so I’m using that construction science.

Each piece takes a long time to make. There’s the acquisition of the wood, the seasoning of the wood. And then, honestly, a lot of it takes place on its own.

Concrete is kind of like baking. With any craft, the finer the materials, the finer your preparation process.

Some guys get this concrete that looks so smooth it almost looks synthetic, but I’m trying to make it look like stone a little bit. In my mix it’s just local sand and gravel — you can kind of see the aggregate — and cement.

So you’re using almost entirely local materials, then.

It’s all local. Hundred percent.

When we get into the idea of sustainability, part of it’s the ecological footprint of a piece, but I like to think of it also as the longevity of a piece.

These pieces aren’t going anywhere. And hopefully the design stays relevant — that’s my goal, to make something that lasts, with a timeless aesthetic.

Something that I think a lot about is the idea of *terroir***; the essence of a place is imbued in stuff that’s made with those materials. Hearing that you’re making things with entirely local materials — how do you find that the Hudson River, the Hudson Valley, plays out in your pieces?**

It’s a great question, and thanks for introducing the question like that, because as an artist and a maker of things, this series of work where I’m using the local wood is very refreshing for me as an artist, in the fact that it’s the materials, it’s the nature, it’s the lines of the materials, it’s the place itself that’s determining the direction of the piece.

So like with this piece of wood, for instance, this is a mere half of another bench that’s in a private residence up the hill. It’s not me coming along saying, “I need to make an angled bench.” I’m looking at the lines of the wood and saying, okay, this is the line that this piece of wood wants to make, so I’ll do my best to finish that line.

It’s a really beautiful process for me because I go out and find this wood, and the piece is already there — the blueprint of the piece is already there. As I discover this Valley and this land more, looking for things, that’s where the inspiration is coming from. It’s really all from the place.

You said it takes a whole crew of guys to get some of this wood out of the water. Do you identify the piece and then get the guys?

Exactly.

I’ll scout out the pieces, and it depends on where the wood is in the river. The Hudson’s very tidal, we get a three-to-four foot tide shift, so sometimes I’ve got to get in there pretty quickly. If there’s a nice piece of wood I need to get it up out of the tide line and then come back to get it at our leisure.

Concrete Art

Brad and I walk upstairs to another section of his studio, where he keeps some art pieces he’s made.

I’m also an artist and, while I like to think of myself more as a furniture designer, I have more images and ideas and stories that I want to tell.

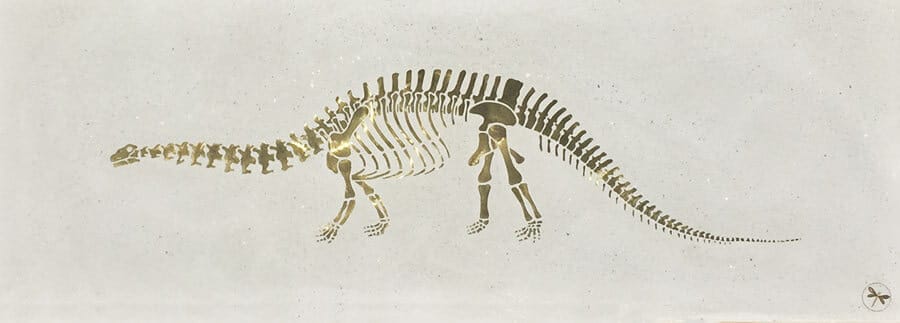

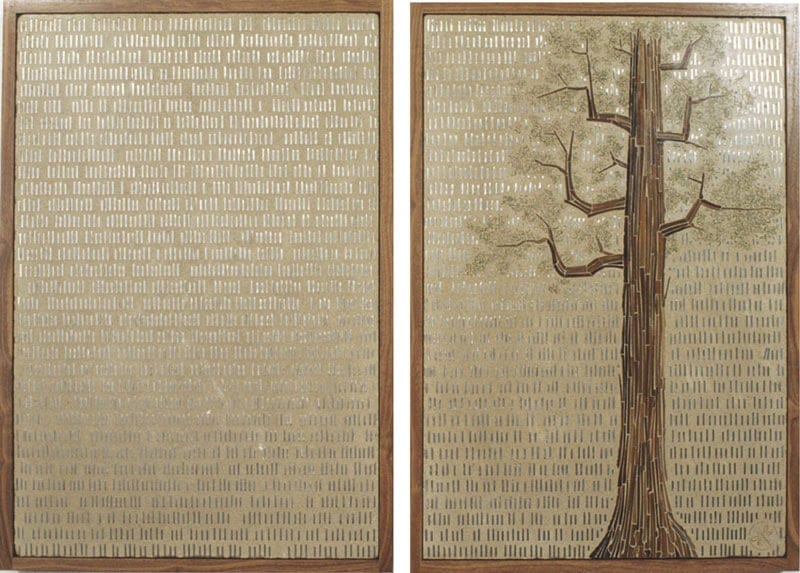

This piece is brass inlaid into concrete. I’ve got some epic, megalithic stories I want to tell.

I’ve been doing this kind of artwork for about 20 years. I wouldn’t say it’s heavily collected, but I’ve sold pieces and people have them all over the country, as well as a couple of international pieces.

How long have you been doing furniture?

I’ve gone through a few incarnations with my furniture. This series, using the raw wood and concrete, is about 5 or 6 years. But these other pieces are about 10 years old. I call that etched concrete — it’s actually sandblasted.

I’ve always been making furniture too, but this new line has a life of its own and it seems to be — and I hate to use such economic terms — really keyed into where the market is right now.

Art is so specific, and the art world is so elusive. Getting into it is a lot about connections or luck, whereas design is based more on the quality of the craftsmanship. It’s a little more of an open market, at least to me. I’ve had more access to the design market than the art market. And since these pieces are so much fun to make, I just go with it.

The Philosophy of a Mermaid Bench

We start walking to the house, where Brad has several finished pieces situated. We pass a set of half-wood, half-concrete sculptures that he describes as “mermaid totems.”

Where does the name mermaid come from?

There’s kind of a living quality. They’re half aquatic — half of the land, half of the water.

Half organic, half engineered-looking.

Exactly. And that’s part of what I’m going for. I love juxtaposition. Even in my art, I try to juxtapose city and country, hard and soft, light and dark, rustic and modern. It creates a movement in the piece. With raw-edged wood in general, I find that a lot of people are working with raw unfinished wood now.

What I like to see is if it’s a really raw piece of wood, but then the carpenters’ done some very fine joinery, some really precise butterfly joints somewhere. Something that actually elevates it.

This is the newest series I’m working on — more planes of the wood. I’ve got some coffee tables I’ve made. I want to scale up to dining table size, given the right client. And I’ve also got chairs based on a similar concept.

We look at one more bench.

There’s a little bit of a seam on this one. I could come back and plane it to get it perfectly smooth. That’s easy to do, but I’d kind of rather have them be two different things.

It’s more honest, somehow.

I find that when it’s a little too perfect, it starts to lose that terroir. It can start to look a little manufactured.

Starts to look a little Pier 1 Imports.

It does! And it’s funny, those guys are always one step behind. I used to do this glass inlaid in concrete. I’m not saying they’re necessarily copying what I’m doing, but some of us concrete guys were doing these thin finishes of concrete over wood frames, and a year or two later you’ve got the box stores doing very similar things.

You can’t fake this. That’s the thing — it just does take a lot of time. Even just finding driftwood that looks like this… that takes time.

I feel like there are so many people who are desperate to “scale up” their operation, but something like this you can’t really scale because you can’t manufacture driftwood. It’s something that exists and you find it, and then you figure process around it. Your process is the same as the cement — it fits around something that’s organic and already exists.

That’s why, as a maker of things, it’s so refreshing for me: I don’t have to go out there like, “Oh, this is what I’m going to make.” You find it and it’s there.

I could scale up in the fact that I could have more guys and we could bring in more wood. I could make two or three at a time. But I don’t think it could ever really be a mass market thing, just because it would be hard to get it down under 40 or 50 hours.

Any frustrations living and working in the Hudson Valley?

Absolutely. I think we’re still reliant on New York City. It seems like our towns — Beacon, Garrison, Cold Spring — there’s a lot of wonderful grassroots movement and growth happening, but I think if NYC wasn’t in the equation the market here would just vanish.

I think many other entrepreneurs in the area find it difficult to run a business here. The weekends, for instance, can be really busy for retail businesses, but the weeks are very slow. It’s tough to be in the economic sphere of Manhattan but without the sheer volume of people. Prices are practically as high here, but there’s just not the volume.

But that’s why we love it, too. That’s why we choose to live here. I’m not trying to make this place busier, but it’s a little frustrating to get something off the ground.

Maybe in a different place things can take off a little quicker.

What is it that attracted you to the Hudson Valley?

We’ve been in Garrison about 15 years; we’ve been in this home for about 8 years, we were at another property in Garrison before that.

I grew up in New Jersey, and then I worked in the City, but my dad’s family is from Poughkeepsie.

Partially because my dad’s from Poughkeepsie, and I grew up in north/central New Jersey. That family’s been there for four or five generations, so part of it’s just in me. I remember when my wife and I rediscovered it, it felt like coming home.

What was in my mind was, as a kid, driving down Route 9D. I remember these forested hills, I remember Osborne Castle up there. It’s a special place. Traveled the whole world, and it’s unique to find this combination of natural beauty with culture and sophistication. I find it to be unique in the world.

This interview has been edited.